In Europe each person is currently generating on average half of tone of household waste per year. Although the management of the waste continues to improve in the EU, the significant amount of potential, valuable secondary raw materials such as metals, wood, plastics, paper and glass are lost in waste streams. Turning waste into a resource is one key to a circular economy. This article analyses current waste management trends in selected Central Baltic counties, i.e. Finland, Sweden, Latvia and in Russia.

Authors: Shima Edalatkhah and Lea Heikinheimo

European legislation as key driver to improve waste management

The European Union’s approach to waste management is based on the waste hierarchy which sets the following priority order: prevention, (preparing for) reuse, recycling, recovery and, as the least preferred option, disposal (which includes landfilling and incineration without energy recovery) (European commission 2019).

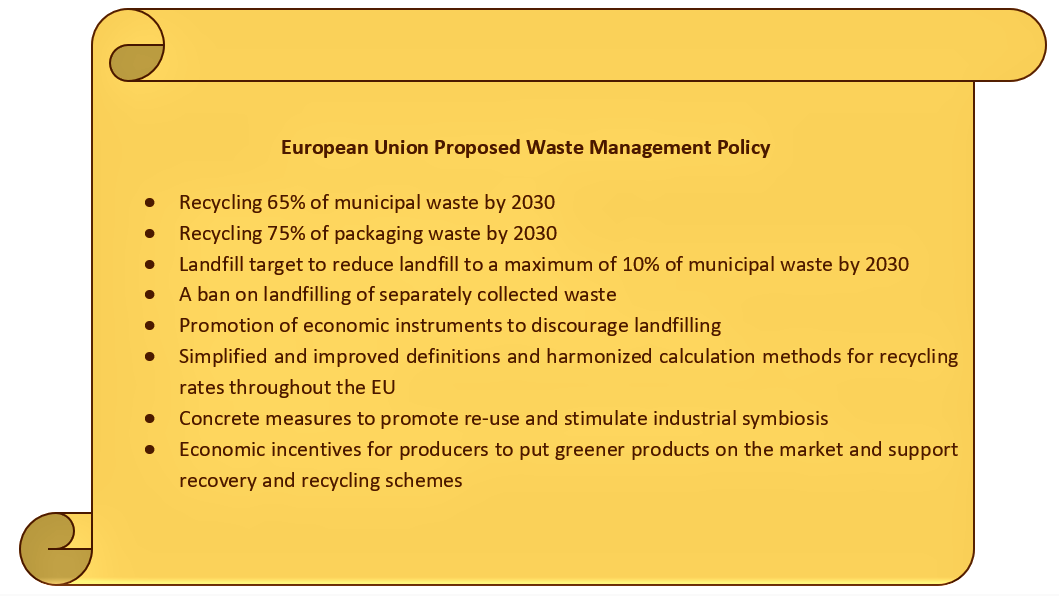

The European Commission has set stricter regulations on waste separation, recycling and landfilling. The proposed key points by EU waste policy as the major instrument in waste management include the following, as listed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The EU Proposed Waste Management Policy (Bremere 2011))

Waste Management in Finland, Sweden, Latvia and Russia

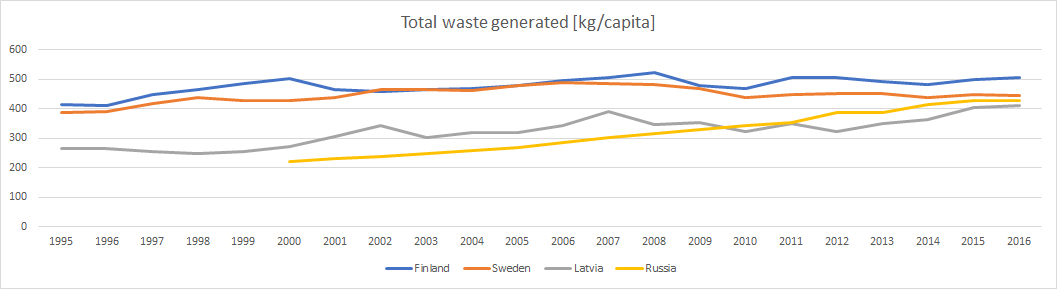

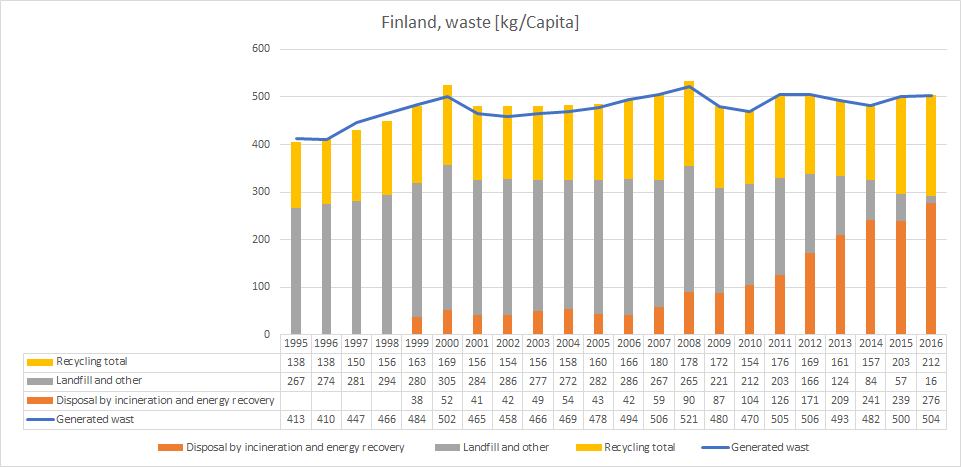

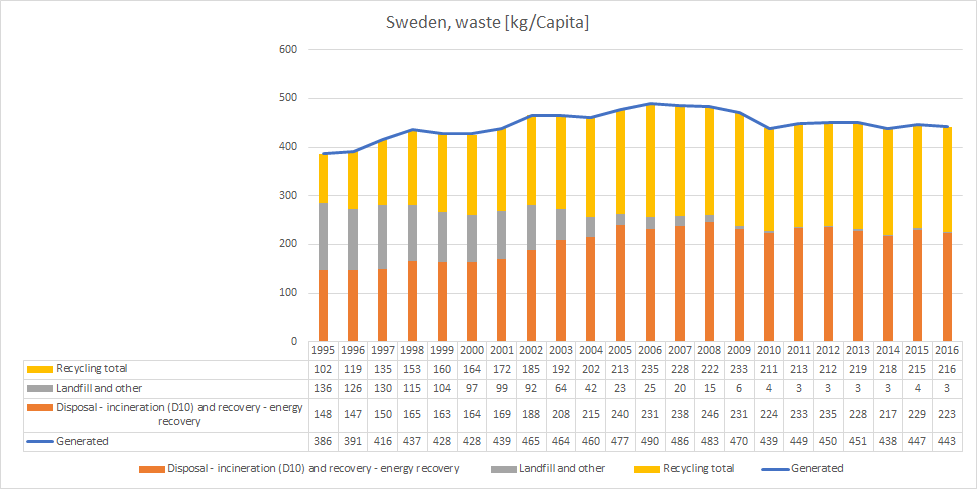

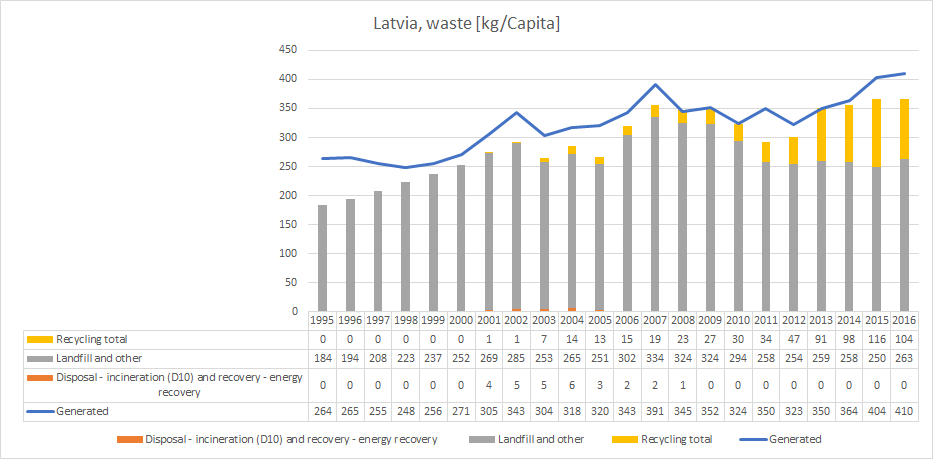

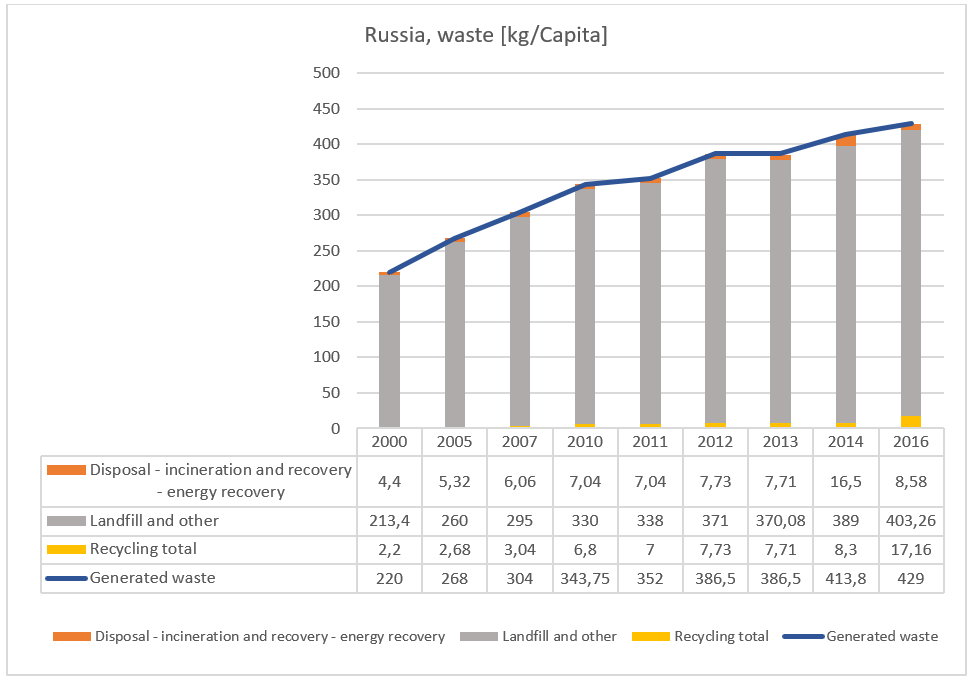

Eurostat keeps track of statistics on waste management in the European Union. Visualizing this data can help in the understanding of the overall difference among Latvia, Finland, Sweden and Russia. This also highlights the shift that has already taken place in Finland and Sweden.

The total waste generated is the first trend. These numbers give us a basic idea of the input problem. This input is surprisingly similar in these countries nowadays. The national data on waste generated per person had varied greatly in previous years, but in year 2016 Swedish, Russians and Latvians produced nearly the same amount of waste, i.e. 400 kg/capita, respectively. Finns produced 500 kg/capita per year (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Total Waste Generated in Finland, Sweden, Latvia and Russia. (Eurostat 2018)

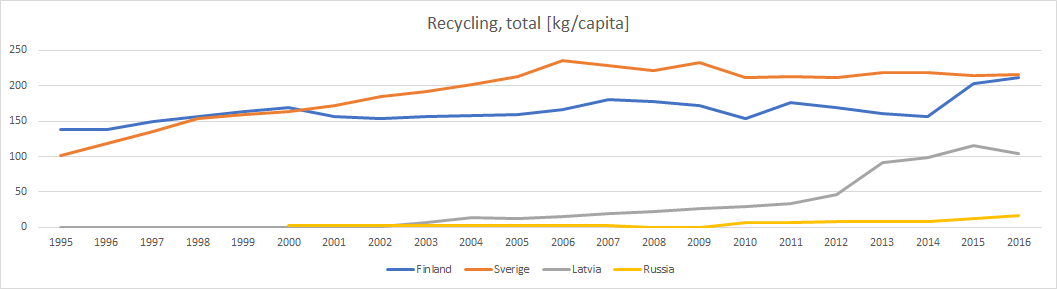

Secondly, the recycling trend matters as the result of environmental awareness, accessibility and culture. (Eurostat 2018) Latvia shows an impressive trend starting from 2012 while Sweden has a steadier incremental growth. In Latvia, the company The Latvijas Zalais punkts has been promoting environmental education and caring for clean and tidy environment for 15 years, thus contributing to the growing trend (Figure 3). (The Latvijas Zalais punkts 2019)

Figure 3. Total Recycling in Finland, Sweden, Latvia and Russia. (Eurostat 2018)

Third, we look deeper into the landfill trend. This is the output of the system. In order to change this output, a holistic view of the problem is needed. The 10% EU goal of landfilling was reached in Sweden already in 2004 and in Finland in 2015 (Figure 4). (Eurostat 2018)

Figure 4. Landfilling in Finland, Sweden, Latvia and Russia. (Eurostat 2018)

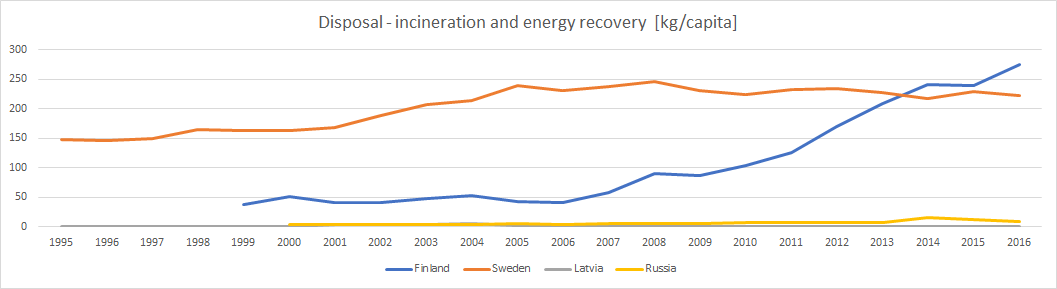

Fourth are the trends for incineration, which is the process of simply burning waste in a controlled way. This process accounts for 50% of waste treatment in Finland and Sweden. The idea is to take advantage of the heat generated and sending this back to the nearby community. (Statistics Finland 2018)

Figure 5. Disposal – incineration and energy recovery in Finland, Sweden, Latvia and Russia. (Eurostat 2018)

Waste Treatment in Finland and Sweden

The total amount of waste in Finland is about 2.4 to 2.8 million tons per year. Finland’s population was 5.54 million in 2018. Considering the amount of waste and inhabitants, the amount is about 500 kilograms per inhabitant per year. Based on a long-term plan of waste management in Finland specifically after 2000, there is currently a dramatic cut down of the number of landfill sites to less than 3% following the outstanding competition over recovery of waste to both energy production and material recovery. (Statistics Finland 2018)

Figure 6. Waste Treatment in Finland. (Eurostat 2018)

As the above statistics illustrate, within a period of 14 years, the municipal waste turned to a significant energy fuel for district heat production. The energy recovered municipal waste include biocomponents like wood, paperboard, cardboard and food waste. (Statistics Finland 2018)

The trends in Finland and Sweden is a trend of steady improvement. The rate of landfill has shrunk by the small increase in recycling and large increase in incineration and energy recovery. At the same time the total waste generated seems to be at a standstill.

Figure 7. Waste Treatment in Sweden. (Eurostat 2018)

Waste Treatment in Latvia and Russia

An interesting increase in generated waste for the last 4 years can be seen in Latvia. The increase is 27% (2012-2016). At the same time, the amount of landfill did not grow by more than 3%. This might be an indicator that the process of the landfill is not seen as the solution when more waste is produced. This is a good thing. More landfill could be an easy way when demand rose. The data does, however, not show where the increase of waste went. No increase in other waste treatment is shown and the data from Eurostat does not add up (Figure 8).

The missing piece between the bars and the line can be explained as a difference in waste generated vs waste treated. However, we do find it very unlikely that the perfect match in 2008, 2009 and 2010 are the result of near 100% treatment. If so the big drop in 2011 should be investigated. The problem is probably due to difference in reporting.

Obviously, the level of incineration and energy recovery needs to increase significantly if the 2030 target is to be reached. Finland´s increase of incineration and energy recovery from 2006 to 2016 is 234 kg/capita. This increase needs to happen in Latvia as well. The 2030 target is not an impossible goal.

Figure 8. Waste Treatment in Latvia. (Eurostat 2018)

The situation in Russia is as follows: as the total amount of waste generated is increasing, so are both the amount of landfill waste and landfill volume. The amount of recyclable waste in 2016 has doubled, which may indicate the beginning of a positive trend. But the share of recyclable waste is extremely small, it is a big problem for Russia now. (Eurostat 2018)

Figure 9. Waste Treatment in Russia. (Eurostat 2018)

The results of this study indicate that there is a positive trend of waste management in all case countries. The amount of new landfilling in Sweden and Finland is nearly about zero, partly due to the ban on landfilling of organic waste. There is still a challenge to reach the target value of 65% of recycling of municipal waste by 2030.

Meanwhile in Latvia, the household waste which is not recycled, is landfilled. There has been an outstanding growth in waste recycling though since 2012. In Latvia, it has been discussed whether they should build waste incinerators, or should they use landfills in mining. As the landfill mining can be considered as a part of the wider view of a circular economy, in recent years activity for secondary raw material recovery has received growing interest in EU area and globally. (Särkkä et al. 2018) Russia has recently had positive paces toward improvement in waste management and has high potentials to progress in the future.

References

Bremere, I. 2011. Improving Waste Prevention Policies in the Baltic States. Assessment and Recommendations. Hamburg: Baltic Environmental Forum. [Cited 15 Nov 2018]. Available at: http://bef-de.org/fileadmin/files/Publications/Waste/activity4-1-1_recommendations_waste-prev.pdf

European Commission. 2019. Waste. Environment. [Cited 15 Nov 2018]. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/waste

Eurostat. 2018. EU Open Data Portal. [Cited 15 Nov 2018]. Available at: https://data.europa.eu/euodp/data/dataset/KvzJCOjr8R9HkDIubruA

Interreg Europe. 2018. Effective municipal waste source. [Cited 15 Nov 2018].

Available at: https://www.interregeurope.eu/policylearning/good-practices/item/234/effective-municipal-waste-source-separation-and-recovery-paeijaet-haeme-region/

Statistics Finland. 2018. Municipal Waste Management. [Cited 15 Nov 2018].

Available at: https://www.stat.fi/til/jate/2016//jate_2016_13_2018-01-15_tie_001_en.html

Särkkä, H., Ranta-Korhonen, T. & Hirvonen, S. 2018. Municipal solid waste landfill as a potential source of secondary raw materials: Case Metsäsairila, Mikkeli. In: Aarrevaara E. & Harjapää A. (Eds.). Smart Cities in Smart Regions 2018: Conference Proceedings. Lahti: Lahti University of Applied Sciences. The Publication Series of Lahti University of Applied Sciences, part 39. 224-231.[Cited 14 Apr 2019]. Available at: URN:NBN:fi:amk-2018091815195

The Latvijas Zalais punkts. 2019. About us. [Cited 14 Apr 2019]. Available at: http://www.zalais.lv/en/about-us/

Authors

Shima Edalatkhah is an International Business Student at Lahti University of Applied Sciences

Lea Heikinheimo, D.Sc. (Tech), works as a Principal lecturer at LAMK, Faculty of Technology. She is also the Manager of the Crea-RE project.

Illustration: https://pxhere.com/en/photo/815927 (CC0)

Published 29.5.2019

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Interreg Central Baltic Program for the funding of the projects “Crea-RE Creating aligned studies in Resource Efficiency”.

Also, we would like to thank the partners and all the participants of the Crea-RE project who helped with data collection.

Reference to this publication

Edalatkhah, S. & Heikinheimo, L. 2019. Waste Management Trends in Selected Central Baltic Countries and in Russia. LAMK Pro. [Cited and date of citation]. Available at: http://www.lamkpub.fi/2019/05/29/waste-management-trends-in-selected-central-baltic-countries-and-in-russia/